I hate the salt burn, the snot dripping, the swollen nose. I hate crying.

But I need one right now. I’m being led by strange waters and trying to stay dispassionate. Sometimes the dry land turns muddy, the hand holding back the waters slips. The sojourning towards a pasture land a recursion back into cold desert nights.

But I wax poetic.

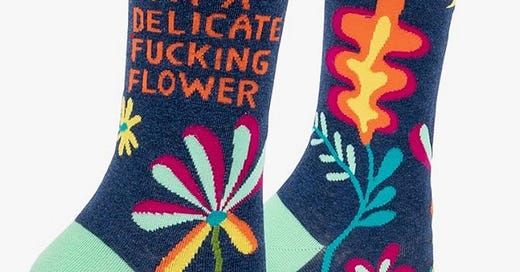

There’s a hole forming in the right sock from the set I bought my sister Ruth. I’m trying to decide if I should darn it and keep wearing it, or put it in the chest, a slightly unstable bit my husband found for twenty bucks at a charity shop in Pennsylvania. I could walk over to my favorite shop, Vons, and replace that sock with a full pair.

Ruth’s body is returning to the earth from which it came, that sock surely being eaten by bacteria some time back.

She hated matching socks. Life’s too short to worry about matching socks, she used to say. After she died, I took up her ethos—my orderly personality needed to lose some of its obsessions.

You young people, my OBGYN said last July when I wore one hot pink-tinged running sock and a neon yellow one on the other foot at my appointment. I was otherwise naked except for the gown open at the back. He’s my age. I had to explain.

Oh, this is for my sister.

I stopped myself from saying she died seven years ago.

I’ve been working on a third iteration of a book that is tied up in her death.

This time I have help from some of the generous humans I’ve come to see as the Spirit at work in my world. (Here’s the first book from our group and you will love it.) And we’re all writing about death and grief. I was getting ready to read Steve’s work, girding my loins after turning in my newspaper column, when my husband David walked in with a look.

Drew called to say that Father James told his parish he has incurable blood cancer after liturgy this morning.

Shit.

Drew is a friend in a parish in Illinois. His priest, Father James, has served with David and me at church camp for years, but long before I met him, I knew his family through his daughter. While we were broke as a joke in seminary, his daughter’s parish provided an embarrassment of Christmas gifts. The next year, the H1N1 virus swept the nation and she died.

We met him that summer. He’d learned to navigate grief and walked a path I now follow. Before I met him, I used to pray St. Teresa of Calcutta’s words, God, break my heart so completely that the whole world falls in.

And God did. There’s a cautionary tale for you.

At camp, the priests visited one cabin each night to do a talk (or play silent football). Father James came to talk about grief. Mostly he ministered to the counselors. One had lost three babies at 16-20 weeks. She’d held each fist-sized, onion-skinned beautiful baby, mourning both her body and the loss.

Father James just busted into the kitchen every day and did the work of the kitchen staff. He beat me in memorizing campers’ names, and I was the teacher on staff. That’s my forte. I can’t imagine the world without him.

Now, I’m foreseeing the future and thinking of Steve’s submission to our writing group.

At some point in your life, each death carries the weight of all the others, wrote Steve.

So true. I learned that truth before losing Ruth, but after David’s dad died of pancreatic cancer in 2005. A beloved monk at the seminary was talking with a friend of mine, weeping and remembering the death of her husband just a couple of years earlier.

A light mist was falling on us outside of the monastery church. A family had asked the priest to pray a service called panikhida, a remembrance service where a sweet bulgar wheat dish is served at the end.

Why am I so upset? She’d asked him.

Every death, even one you only heard about, can trigger grief. Father Gabriel knew this because he’d lived it and ministered through it.

Her husband had been a training pilot and his wealthy student switched the fuel tank from the full to the empty in his plane. The wealthy student of her husband thought he knew better how to operate the Cessna he’d just bought. That rich man and her husband burned up just outside of Scranton, PA. Her son and mine were months apart and served together in the altar, two six-year-olds.

It’s not the years, it’s the proximity after death, the broken relationships of the surviving that are wearing me down.

Last Friday, as my five-year-old grandson and I drove back from school, he and I got to talking about the relationship between David and Meemaw, my mother-in-law. She lives with us, and she’s everyone's favorite saint, at least anyone who knows her. I had one of those obligatory life conversations with the young about who’s related to whom. My grandson is named for Meemaw’s husband, Dean, and he calls David “Papaw.”

Papaw is Meemaw’s son. You are named for Papaw’s dad, I explained. You would have loved him. He was funny. He loved kids. He could talk about farts and cars for hours.

Why can’t I see him? My grandson asked.

He died, honey, when your Uncle Alex and your mom were little.

We did the recursive conversation spiral about how Papaw’s dad died. Is he alive now? my grandson asked. (He’s alive in heaven waiting on you, I said. That’s good. This story was getting sad, he replied, glad that Papaw’s dad is in heaven.)

The last thing he said, that I know of, was “I love you” to your mom and Uncle Alex. My father-in-law’s breath sounded like a steam train but he found the best way to curve his mouth to utter something discernable. I was convinced he meant it for everyone in his family. He loved them all so much. I’ve never met people like David’s parents. They don’t put conditions on love. It’s the closest I’ve met to God, and that’s a lot considering my grandpa had that kind of bigness, but even he was restrained by some kind of theological idea of exclusion.

I remember driving my father-in-law, who looked like little Cindy Lu-who’s dad, to one of his treatments. Just after he stepped out of our car, he stumbled. I rushed to his side of the car to catch him in my arms. The radiation and chemo reduced him to ash and instability. I knew then that he was losing the battle. I started mourning then but kept it to myself. One can always hope.

I recall the moment I knew Ruth wouldn’t win.

It’s bad. She had a new cancer in her mouth, not related to her rectal cancer. It’s the secondary cancer that will kill you.

Not always but often enough. Sometimes it’s the primary cancer that gets you.

Steve’s brother survived seven years of a slow-growing brain tumor.

Seven years I met my friend S. I’m going to not use her full name, but her husband and mine are both clergy and both stayed in the same dorm at the same evangelical college decades ago. Both are now priests in liturgical traditions and in our tiny little town.

Almost a year ago, as S and I prepared to leave Louisville after a girlfriend’s getaway, on our final stop at Angel’s Envy in Louisville, she spoke words I heard Ruth say.

I don’t expect to outlive my family.

Shit. I’ve heard those before.

The first night I saw S, we were attending a concert of a band we’ve both loved since we met our spouses. She was on the phone, looking stressed. Her husband had one foot in her space, the other half in the air trying not to fear.

S was about to have her brain tumor Zed removed.

Zed was a fucker who was not supposed to be invasive cancer.

We met S and her hubby— we called him Phubbs from college days— later and then they became the kind of people who make your faith stronger.

Last December, I cried when she said what she said.

I’ve heard that before, I said. I wiped the moisture leaking from my eyes.

I made her feel a little bad, but I saw the truth of it. She knows her life span. Ruth did too.

Ruth said, I can’t count on living for five years. I probably won’t see my kids graduate. Ruth was stage 4 when she was diagnosed, which she kept to herself, letting us realize far too late.

Tonight as I finish the first read of Steve’s final chapters about his brother’s death of slow-growing brain cancer, as I process losing a priest I know and keep holding out for decades more for S, I am undone.

Of course, my soul is crying out about dozens over other griefs, but I want to stand here and document this moment.

Before I read Steve’s chapters I read a piece on AI and authorship. Technology and this era of cult-personality-worship and social media toxicity and concerns creep on my desire for dispassion. I am trying not to live in despair. Kick me, but grief and the hope of something eternal are all I have left at the end of the night.